About

Welcome to Clan Muir Society International

The purpose of this site is to share historic information about Clan Muir to their clan members, and anyone who is interested in learning about Clan Muir. . Clan Muir is one of the most powerful, wealthiest, large, famous and ancient clans in Scotland. Come with us on a journey to discovering who Clan Muir was, and discovering who they came from. Clan Muir is probably the only clan that continuously went thru hardship and much suffering. Many times clan Muir have been betray, been backstab, many clans hated and were jealous of us, and many tried to get rid of us but continue to fail. We are claimed by Clan Campbell, Clan Gordon, Clan Leslie, Clan Boyd, and Clan Grant as a Sept, but because with the resurgence of Clan Muir, we are happy to call ourselves a sept of no other Clan, but a clan upon itself and invite all Clan Brothers and Sisters home.

Muir name meaning:

Muir in Gaelic means: Large or Big Mor in Gaelic means: The Great

Muir in Middle English means: Moor or Heath Moore in Irish means: Noble or stately

Muir in Pictish means: By the Sea

Scottish Mottos

Clan Muir- Durum patientia frango

Moir Mottos:

Non sibi, sed cunctis (Not just for self, but for all).

Mediocriter (with moderation) or Sur experance (upon hope).

Major opima feret (Let the worthier carry off the prize).

Virtute non aliter (by virtue, not otherwise).

Non sibi, sed cunctia (For all, not himself).

Moir of Lockie/ Leckie- Ne oublie

Irish O'Mordha Mottos

O' More of Laois/ Lexi- Motto: Conlon Abú

Moore (Earl of Drogheda)- Motto: Fortis cadere cedere non potest. - The brave may fall, but cannot yield.

Moore (Earl of Mountcashel- Motto: Vis unita fortior.- "United Strength is Stronger

Moore (Ballina Co. Mayo and Alicante, Spain)- Motto: Fortis cadere cedere non potest.- The brave may fall, but cannot yield.

Moore of Ballymacrue-Motto: Perseverando et cavendo.

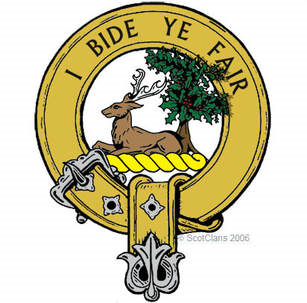

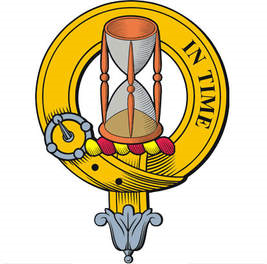

Clan Muir's Cap Badge:

Clan's Crest Badge: This is the crest badge of clan Muir. This is the clansman's badge, comprised of the crest from the chieftain's coat of arms, surrounded by a belt and buckle with the clan's motto. It may be worn by all members of the clan. The crest is A savage head couped Proper.

Motto: Durum Patientia Frango ( I overcome difficulty by patience/By patience I break what is hard).

Region of Scotland: Highlands, Lowlands, Galloway, and Scottish Borders

Pipe music: The March of the king of Laois

Clan Plant: The Rowan Tree

This is the clan's plant " The Rowan Tree"; The bonny rowan tree is a hardy little mountain ash tree with soft, delicate, fern-shaped leaves. Often planted as an ornamental tree for its beauty, it is also useful in providing an excellent source of shade in the summer. The rowan enjoys a rich history in its native land. Adored by many, it has been planted for its protective powers in mountain and cottage gardens for centuries. It is believed to ward off witches and evil spirits with its mystical virtues. It is also revered as the “Tree of Good Luck.” The rowan tree’s greatest virtue may simply be its benevolent gift of beauty through the seasons.

Clan Muir's Tartans

Clan Muir has four tartans in which the clansmen can wear.

Clan Muir Modern Tartan

Clan Muir Ancient Tartan

John Muir Tartan ( Dress)

Laois Tartan ( O'Mordha Tartan)

Laois Tartan 2 ( O'Modrha)

Longmuir Tartan

Coat of Arms of Clan Muir:

Chieftain's coat of Arms- Muir of Rowallan with the coat of arms of Comyn.

Chieftain's coat of Arms- Muir of Rowallan with the coat of arms of Comyn.

Coat of Arms of Muir of Rowallan.

Coat of Arms of Muir of Rowallan.

The Moirs coat of Arms of Aberdeen and the Highlands.

The Moirs coat of Arms of Aberdeen and the Highlands.

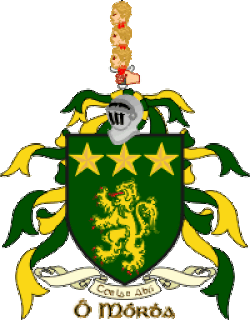

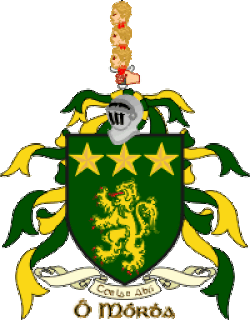

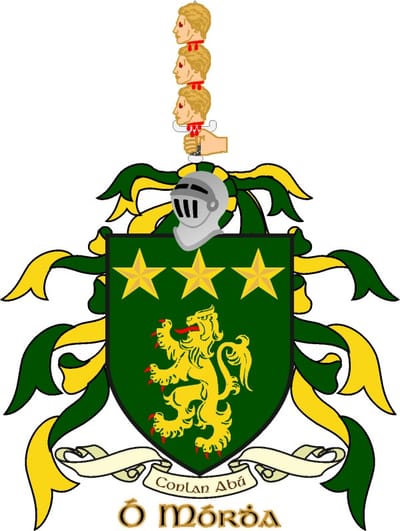

The Irish O'Mordha clan's coat of arms. The lion is the symbol of the Milesian tribe and also the symbol of the tribe of Judah; in which the Moores are apart. The three stars that are shown in this coat of arms as well the coat of arms on the chieftains of clan Muir of Rowallan. The stars may represent the holy trinity.

The Irish O'Mordha clan's coat of arms. The lion is the symbol of the Milesian tribe and also the symbol of the tribe of Judah; in which the Moores are apart. The three stars that are shown in this coat of arms as well the coat of arms on the chieftains of clan Muir of Rowallan. The stars may represent the holy trinity.

Other website:

https://kierenmuir.weebly.com/

The purpose of this site is to share historic information about Clan Muir to their clan members, and anyone who is interested in learning about Clan Muir. . Clan Muir is one of the most powerful, wealthiest, large, famous and ancient clans in Scotland. Come with us on a journey to discovering who Clan Muir was, and discovering who they came from. Clan Muir is probably the only clan that continuously went thru hardship and much suffering. Many times clan Muir have been betray, been backstab, many clans hated and were jealous of us, and many tried to get rid of us but continue to fail. We are claimed by Clan Campbell, Clan Gordon, Clan Leslie, Clan Boyd, and Clan Grant as a Sept, but because with the resurgence of Clan Muir, we are happy to call ourselves a sept of no other Clan, but a clan upon itself and invite all Clan Brothers and Sisters home.

Muir name meaning:

Muir in Gaelic means: Large or Big Mor in Gaelic means: The Great

Muir in Middle English means: Moor or Heath Moore in Irish means: Noble or stately

Muir in Pictish means: By the Sea

Scottish Mottos

Clan Muir- Durum patientia frango

Moir Mottos:

Non sibi, sed cunctis (Not just for self, but for all).

Mediocriter (with moderation) or Sur experance (upon hope).

Major opima feret (Let the worthier carry off the prize).

Virtute non aliter (by virtue, not otherwise).

Non sibi, sed cunctia (For all, not himself).

Moir of Lockie/ Leckie- Ne oublie

Irish O'Mordha Mottos

O' More of Laois/ Lexi- Motto: Conlon Abú

Moore (Earl of Drogheda)- Motto: Fortis cadere cedere non potest. - The brave may fall, but cannot yield.

Moore (Earl of Mountcashel- Motto: Vis unita fortior.- "United Strength is Stronger

Moore (Ballina Co. Mayo and Alicante, Spain)- Motto: Fortis cadere cedere non potest.- The brave may fall, but cannot yield.

Moore of Ballymacrue-Motto: Perseverando et cavendo.

Clan Muir's Cap Badge:

Clan's Crest Badge: This is the crest badge of clan Muir. This is the clansman's badge, comprised of the crest from the chieftain's coat of arms, surrounded by a belt and buckle with the clan's motto. It may be worn by all members of the clan. The crest is A savage head couped Proper.

Motto: Durum Patientia Frango ( I overcome difficulty by patience/By patience I break what is hard).

Region of Scotland: Highlands, Lowlands, Galloway, and Scottish Borders

Pipe music: The March of the king of Laois

Clan Plant: The Rowan Tree

This is the clan's plant " The Rowan Tree"; The bonny rowan tree is a hardy little mountain ash tree with soft, delicate, fern-shaped leaves. Often planted as an ornamental tree for its beauty, it is also useful in providing an excellent source of shade in the summer. The rowan enjoys a rich history in its native land. Adored by many, it has been planted for its protective powers in mountain and cottage gardens for centuries. It is believed to ward off witches and evil spirits with its mystical virtues. It is also revered as the “Tree of Good Luck.” The rowan tree’s greatest virtue may simply be its benevolent gift of beauty through the seasons.

Clan Muir's Tartans

Clan Muir has four tartans in which the clansmen can wear.

Clan Muir Modern Tartan

Clan Muir Ancient Tartan

John Muir Tartan ( Dress)

Laois Tartan ( O'Mordha Tartan)

Laois Tartan 2 ( O'Modrha)

Longmuir Tartan

Coat of Arms of Clan Muir:

Chieftain's coat of Arms- Muir of Rowallan with the coat of arms of Comyn.

Chieftain's coat of Arms- Muir of Rowallan with the coat of arms of Comyn. Coat of Arms of Muir of Rowallan.

Coat of Arms of Muir of Rowallan. The Moirs coat of Arms of Aberdeen and the Highlands.

The Moirs coat of Arms of Aberdeen and the Highlands. The Irish O'Mordha clan's coat of arms. The lion is the symbol of the Milesian tribe and also the symbol of the tribe of Judah; in which the Moores are apart. The three stars that are shown in this coat of arms as well the coat of arms on the chieftains of clan Muir of Rowallan. The stars may represent the holy trinity.

The Irish O'Mordha clan's coat of arms. The lion is the symbol of the Milesian tribe and also the symbol of the tribe of Judah; in which the Moores are apart. The three stars that are shown in this coat of arms as well the coat of arms on the chieftains of clan Muir of Rowallan. The stars may represent the holy trinity.Other website:

https://kierenmuir.weebly.com/

The Milesian Tribe

Clan Muir has to be one of the most fascinating, unique, powerful, wealthiest and influential clans in Scotland. There are two main questions that has to be answer; the first question is What origins did the Mure family/ clan came from? And what's their history about? The reason these questions are so popular, is that clan Muir's history seem to have disappear over time. Well, after many years of research that I have done; I can say for certain that I can answer those two questions. According to some people that we originate in the Strathclyde Kingdom, others say that we came from the Picts of Scotland and Ireland and there are few other legends and myths about our origins. The fact is that all the variant spellings of Muir, Mur, Mure, Mor, More, Moore, ect... throughout the world, are all linked to one tribe and one point of origin.

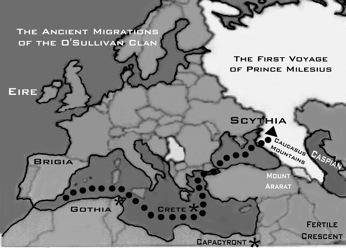

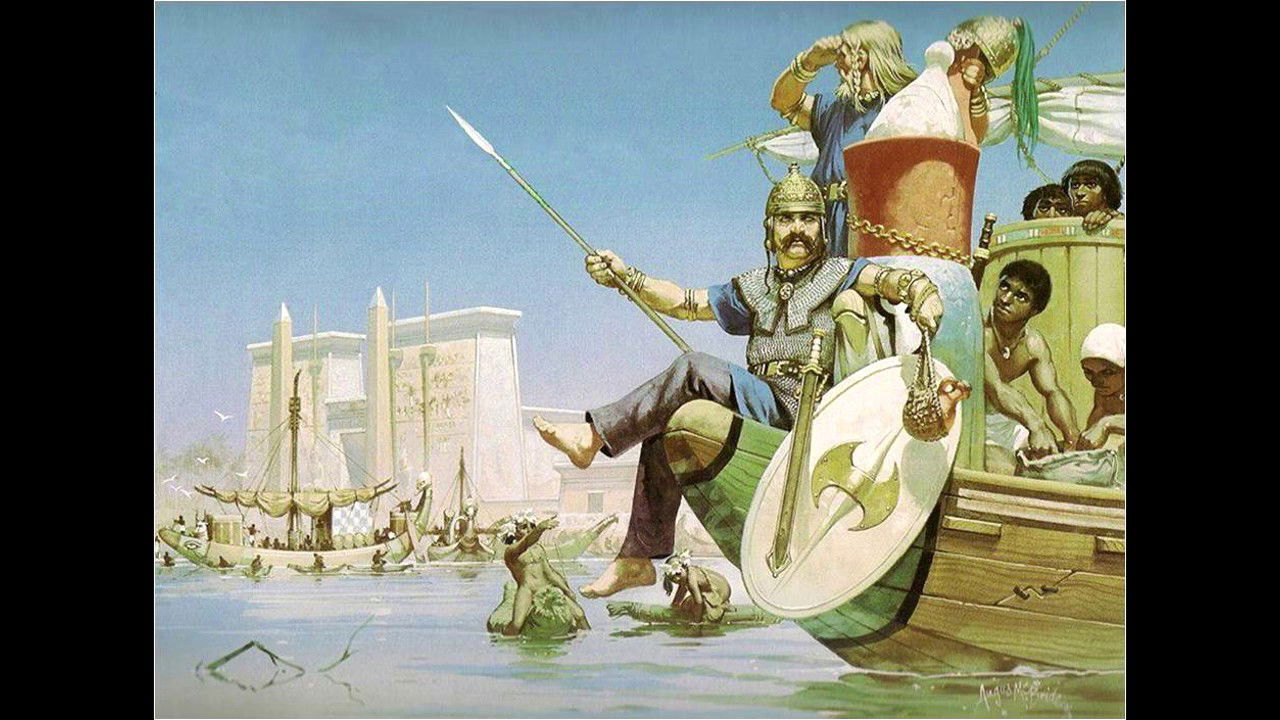

You might ask what Tribe did the Muirs came from, and that tribe is called " The Milesian Tribe", in which the Celt race came from. The Milesians point of origin is located in Scythia. These Scythians were among the earliest people to master mounted warfare. These Scythians eventually became one of the ten lost tribes of Israel, The Milesian, then became the Celtic race, then became the Galicians, Irish and then the Scottish people. These Milesians became excellent warriors as well as wanders, and prosperous in construction, agriculture, and many other things. According to legend of the Milesians; that one of their ancestors had been married to the daughter of the Pharaoh of Egypt and is possibly connected with the presence of " Chalybes" ( or Calybes) descendants of Caleb from the tribe of Judah amongst them. The Symbol of the Milesians appears to have been a lion. The lion is also the symbols of the Tribe of Judah and the Irish O'Moores.

The Milesian Tribe

In the Lebor Gabala Erenn, a medieval Irish Christian pseudo-history, the Milesians are the final race to settle in Ireland. They represent the Irish people. The Milesians are Gaels who sail to Ireland from Hispania after spending hundreds of years travelling the earth. When they land in Ireland they contend with the Tuath De Danann, who represent the pagan gods. The two groups agree to divide Ireland between them: the Milesians take the world above, while the Tuath Dé take the world below. They are named after the character Mil Espaine, which is the Irish form of the Latin Miles Hispaniae ("Soldier of Hispania"). Scholars believe that the tale is mostly an invention of medieval Christian writers.

The Lebor Gabala, which was probably first written in the 11th century AD by Christian monks, purports to be a history of Ireland and the Irish (the Gaels). It tells us that all mankind is descended from Adam through the sons of Noah, and that a man named Fenius Farsaid ( descendant of Noah's son Japheth) is the forebear of the Gaels. Fénius, a prince of Scythia, is described as one of 72 chieftains who built the Tower of Babel ( Read Genesis 11:1-9 of the holy bible). Goídel crafts the Goidelic ( Gaelic) language from the original 72 languages that arose after the confusion of tongues. It was said that in his youth, Gaodhal, son of Niul, was bitten in the neck by a snake. He was brought to Moses, who laid his rod upon him and cured him instantly.

The snake bite left a green scar, so Gaodhal became Gaodhal Glas, because Glas means green. Gaodhal Glas also received another blessing, which was that no poisonous snake could live anywhere his posterity lived. At this time, Gaodhal Glas and his descendants painted beasts, birds, etc., on their shields in imitation of the Israelites. Asruth was a son of Gaodhal Glas. He lived in Egypt and governed his colony in peace. Sruth was a son of Asruth. Asruth frequently supported the Israelites against the Egyptians, so shortly after Asruth’s death, the Egyptians attacked Sruth and his followers.

Other ancient sources say that the Egyptians attacked Sruth after the pharaoh was drowned in the Red Sea in pursuit of the Israelites. Other accounts states that while in Egypt; Fennius the Scythian met Moses and helped the Israelites when they were free to leave Egypt after the plagues that has struck Egypt. There were some Israelites who attached themselves to Fennius and travelled with the Milesians. Versions of these legends also claim that they have kept the laws of Moses in Ancient times, and this means that they were Hebrews but also keeping a separate " Scythian" identity were also able to claim descent from Magog, son of

Japhet. It's also claim that one of the Milesian married into the tribe of Judah and settled into the areas of the ten tribes settlement.

Remember the Milesians symbol has been a lion; the same as the Judah tribe. It is also claim that the Milesian tribe wander with the Israelites and Moses for 400 years in the wilderness. The word Celt is the Anglicized form of the Greek word " Keltoi" which means " The people who are different." The Celts are part of the Ten tribes and the Milesians are part of Judah ( which the O'Mordha/ Muir clans are descendants from) and Zarahites. What is interesting is that the Irish Celtic law was based on the Torah and is further confirmation that the Celts are indeed Israelites. If you reject your birth-right as Israelites, then you are insulting God, who gave your birth right to you, along with the Covenant.

Brit ( Berit) means Covenant in Hebrew

Welsh means Man or People of in Hebrew

British means The people of the Covenant in Hebrew

Hebernia ( Ireland) means Hebrew's new land

Heberia- Iberia ( Spain) means Hebrew's land

Below is a Chart in which it claims that our Ancestors came from Zarah's line, in which her father's name is Judah; in which the " Tribe of Judah" was establish. After the chart below, I will give you the exact genealogy that connect it all. The Irish O'Mordhas ( O'Moores), the Scottish Clan Muir and other Moores/ More/ Mor/ Mure/Muir that are found worldwide in India, Mainland Europe are all connected thru the House of Ir.

The Milesian Genealogy

The following genealogy of the Milesian Tribe in which the O'Mordha clan of Ireland came from. Also to mention that the Mores in India and throughout the European Nations such as Austria, Germany, Gaul ( France) Spain, Galicia, England and other nations are from the same Milesian tribe that founded the Irish O'Mordhas, and the Scottish Muirs/ Mures. God the Father, Son, and Holy Ghost, who was from all eternity, did, in the beginning of Time, of nothing, create Red Earth; and of Red Earth framed Adam; and of a Rib out of the side of Adam fashioned Eve. After which Creation, Plasmation, and Formation, succeeded Generations, as follows."--Four Masters. The Scottish Clan Muir hail from Conmael line, brother of Ebric of the line of Ir. The line continues to Ugaine Mor, and all the way to Conaire Mor the founder of the Dal Riata Kingdom in Ireland.

1. Adam & Eve

2. Seth

3. Enos

4. Cainan

5. Mahalaleel

6. Jared

7. Enoch

8. Methuselah

9. Lamech

10. Noah divided the world amongst his three sons, begotten of his wife Titea: viz., to Shem he gave Asia, within the Euphrates, to the Indian Ocean; to Ham he gave Syria, Arabia, and Africa; and to Japhet, the rest of Asia beyond the Euphrates, together with Europe to Gades (or Cadiz).

11. Japhet was the eldest son of Noah. He had fifteen sons, amongst whom he divided Europe and the part of Asia which his father had allotted to him.

12. Magog: From whom descended the Parthians, Bactrians, Amazons, etc.; Partholan, the first planter of Ireland, about three hundred years after the Flood; and also the rest of the colonies that planted there, viz., the Nemedians, who planted Ireland, Anno Mundi three thousand and forty-six, or three hundred and eighteen years after the birth of Abraham, and two thousand one hundred and fifty-three years before Christ. The Nemedians continued in Ireland for two hundred and seventeen years; within which time a colony of theirs went into the northern parts of Scotland, under the conduct of their leader Briottan Maol, from whom Britain takes its name, and not from "Brutus," as some persons believed. From Magog were also descended the Belgarian, Belgian, Firbolgian or Firvolgian colony that succeeded the Nemedians, Anno Mundi, three thousand two hundred and sixty-six, and who first erected Ireland into a Monarchy. [According to some writers, the Fomorians invaded Ireland next after the Nemedians.]

This Belgarian or Firvolgian colony continued in Ireland for thirty-six years, under nine of their Kings; when they were supplanted by the Tuatha-de-Danans (which means, according to some authorities, "the people of the god Dan," whom they adored), who possessed Ireland for one hundred and ninety-seven years, during the reigns of nine of their kings; and who were then conquered by the Gaelic, Milesian, or Scotia Nation (the three names by which the Irish people were known), Anno Mundi three thousand five hundred. This Milesian or Scotia Irish Nation possessed and enjoyed the Kingdom of Ireland for two thousand eight hundred and eighty-five years, under one hundred and eighty-three Monarchs; until their submission to King Henry the Second of England, Anno Domini one thousand one hundred and eighty-six.

13. Baoth, one of the sons of Magog; to whom Scythia came as his lot, upon the division of the Earth by Noah amongst his sons, and by Japhet of his part thereof amongst his sons.

14. Phoeniusa Farsaidh (or Fenius Farsa) was King of Scythia, at the time that Ninus ruled the Assyrian Empire; and, being a wise man and desirous to learn the languages that not long before confounded the builders of the Tower of Babel, employed able and learned men to go among the dispersed multitude to learn their several languages; who sometime after returning well skilled in what they went for, Phoeniusa Farsaidh erected a school in the valley of Senaar, near the city of Æothena, in the forty-second year of the reign of Ninus; whereupon, having continued there with his younger son Niul for twenty years, he returned home to his kingdom, which, at his death, he left to his eldest son Nenuall: leaving to Niul no other patrimony than his learning and the benefit of the said school.

15. Niul, after his father returned to Scythia, continued some time at Æothena, teaching the languages and other laudable sciences, until upon report of his great learning he was invited into Egypt by Pharaoh, the King; who gave him the land of Campus Cyrunt, near the Red Sea to inhabit, and his daughter Scotia in marriage: from whom their posterity are ever since called Scots; but, according to some annalists, the name "Scots" is derived from the word Scythia.

It was this Niul that employed Gaodhal [Gael], son of Ethor, a learned and skillful man, to compose or rather refine and adorn the language, called Bearla Tobbai, which was common to all Niul's posterity, and afterwards called Gaodhilg (or Gaelic), from the said Gaodhal who composed or refined it; and for his sake also Niul called his own eldest son "Gaodhal." [The following is a translation of an extract from the derivation of this proper name, as given in Halliday's Vol. of Keating's Irish History, page 230:

"Antiquaries assert that the name of Gaodhal is from the compound word formed of 'gaoith' and 'dil,' which means a lover of learning; for, 'gaoith' is the same as wisdom or learning, and 'dil' is the same as loving or fond."]

16. Gaodhal (or Gathelus), the son of Niul, was the ancestor of the Clan-na-Gael, that is, "the children or descendants of Gaodhal." In his youth this Gaodhal was stung in the neck by a serpent, and was immediately brought to Moses, who, laying his rod upon the wounded place, instantly cured him: whence followed the word "Glas" to be added to his name, as Gaodhal Glas (glas: Irish, green; Lat. glaucus; Gr. glaukos), on account of the green scar which the word signifies, and which, during his life, remained on his neck after the wound was healed. And Gaodhal obtained a further blessing, namely--that no venemous beast can live any time where his posterity should inhabit; which is verified in Creta or Candia, Gothia or Getulia, Ireland, etc.

The Irish chroniclers affirm that from this time Gaodhal and his posterity did paint the figures of Beasts, Birds, etc., on their banners and shields, to distinguish their tribes and septs, in imitation of the Israelites; and that a "Thunderbolt" was the cognizance in their chief standard for many generations after this Gaodhal.

17. Asruth, after his father's death, continued in Egypt, and governed his colony in peace during his life.

18. Sruth, soon after his father's death, was set upon by the Egyptians, on account of their former animosities towards their predecessors for having taken part with the Israelites against them; which animosities until then lay raked up in the embers, and now broke out in a flame to that degree, that after many battles and conflicts, wherein most of his colony lost their lives, Sruth was forced with the few remaining to depart the country; and, after many traverses at sea, arrived at the Island of Creta (now called Candia), where he paid his last tribute to nature.

19. Heber Scut (scut: Irish, a Scot), after his father's death and a year's stay in Creta, departed thence, leaving some of his people to inhabit the Island, where some of their posterity likely still remain; "because the Island breeds no venemous serpent ever since." He and his people soon after arrived in Scythia; where his cousins, the posterity of Nenuall (eldest son of Fenius Farsa, above mentioned), refusing to allot a place of habitation for him and his colony, they fought many battles wherein Heber (with the assistance of some of the natives who were ill-affected towards their king), being always victor, he at length forced the sovereignty from the other, and settled himself and his colony in Scythia, who continued there for four generations. (Hence the epithet Scut, "a Scot" or "a Scythian," was applied to this Heber, who is accordingly called Heber Scot.) Heber Scot was afterwards slain in battle by Noemus the former king's son.

20. Beouman;

21. Ogaman;

22. Tait, were each kings of Scythia, but in constant war with the natives; so that after Tait's death his son,

23. Agnon and his followers betook themselves to sea, wandering and coasting upon the Caspian Sea for

several (some say seven) years in which time he died.

24. Lamhfionn and his fleet remained at sea for some time after his father's death, resting and refreshing themselves upon such islands as they met with. It was then that Cachear, their magician or Druid, foretold that there would be no end of their peregrinations and travel until they should arrive at the Western Island of Europe, now called Ireland, which was the place destined for their future and lasting abode and settlement; and that not they but their posterity after three hundred years should arrive there. After many traverses of fortune at sea, this little fleet with their leader arrived at last and landed at Gothia or Getulia--more recently called Lybia, where Carthage was afterwards built; and, soon after, Lamhfionn died there.

25. Heber Glunfionn was born in Getulia, where he died. His posterity continued there to the eighth generation; and were kings or chief rulers there for one hundred and fifty years--some say three hundred years.

26. Agnan Fionn; 27. Febric Glas; 28. Nenuall; 29. Nuadhad; 30. Alladh; 31. Arcadh; and 32. Deag: of these nothing remarkable is mentioned, but that they lived and died kings in Gothia or Getulia.

33. Brath was born in Gothia. Remembering the Druid's prediction, and his people having considerably multiplied during their abode in Getulia, he departed thence with a numerous fleet to seek out the country destined for their final settlement, by the prophecy of Cachear, the Druid above mentioned; and, after some time, he landed upon the coast of Spain, and by strong hand settled himself and his colony in Galicia, in the north of that country.

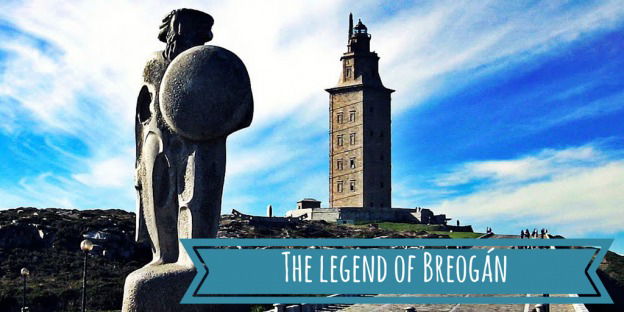

34. Breoghan (or Brigus) was king of Galicia, Andalusia, Murcia, Castile, and Portugal--all which he conquered. He built Breoghan's Tower or Brigantia in Galicia, and the city of Brigansa or Braganza in Portugal--called after him; and the kingdom of Castile was then also called after him Brigia. It is considered that "Castile" itself was so called from the figure of a castle which Brigus bore for his Arms on his banner. Brigus sent a colony into Britain, who settled in that territory now known as the counties of York, Lancaster, Durham, Westmoreland, and Cumberland, and, after him, were called Brigantes; whose posterity gave formidable opposition to the Romans, at the time of the Roman invasion of Britain.

35. Bilé was king of those countries after his father's death; and his son Galamh [galav] or Milesius succeeded him. This Bilé had a brother named Ithe.

36. Milesius, in his youth and during his father's life-time, went into Scythia, where he was kindly received by the king of that country, who gave him his daughter in marriage, and appointed him General of his forces. In this capacity Milesius defeated the king's enemies, gained much fame, and the love of all the king's subjects. His growing greatness and popularity excited against him the jealousy of the king; who, fearing the worst, resolved on privately despatching Milesius out of the way, for, openly, he dare not attempt it. Admonished of the king's intentions in his regard, Milesius slew him; and thereupon quitted Scythia and retired into Egypt with a fleet of sixty sail. Pharaoh Nectonibus, then king of Egypt, being informed of his arrival and of his great valor, wisdom, and conduct in arms, made him General of all his forces against the king of Ethiopia then invading his country.

Here, as in Scythia, Milesius was victorious; he forced the enemy to submit to the conqueror's own terms of peace. By these exploits Milesius found great favor with Pharaoh, who gave him, being then a widower, his daughter Scotia in marriage; and kept him eight years afterwards in Egypt.

During the sojourn of Milesius in Egypt, he employed the most ingenious and able persons among his people to be instructed in the several trades, arts, and sciences used in Egypt; in order to have them taught to the rest of his people on his return to Spain.

[The original name of Milesius of Spain was, as already mentioned, "Galamh" (gall: Irish, a stranger; amh, a negative affix), which means, no stranger: meaning that he was no stranger in Egypt, where he was called "Milethea Spaine," which was afterwards contracted to " Milé Spaine" (meaning the Spanish Hero), and finally to "Milesius" (mileadh: Irish, a hero; Lat. miles, a soldier).] At length Milesius took leave of his father-in-law, and steered towards Spain; where he arrived to the great joy and comfort of his people, who were much harasssed by the rebellion of the natives and by the intrusion of other foreign nations that forced in after his father's death, and during his own long absence from Spain. With these and those he often met; and, in fifty-four battles, victoriously fought, he routed, destroyed, and totally extirpated them out of the country, which he settled in peace and quietness.

In his reign a great dearth and famine occurred in Spain, of twenty-six years' continuance, occasioned, as well by reason of the former troubles which hindered the people from cultivating and managing the ground, as for want of rain to moisten the earth; but Milesius superstitiously believed the famine to have fallen upon him and his people as a judgment and punishment from their gods, for their negligence in seeking out the country destined for their final abode, so long before foretold by Cachear their Druid or magician, as already mentioned--the time limited by the prophecy for the accomplishment thereof being now nearly, if not fully, expired.

To expiate his fault and to comply with the will of his gods, Milesius, with the general approbation of his people, sent his uncle Ithe, with his son Lughaidh [Luy], and one hundred and fifty stout men to bring them an account of those western islands; who, accordingly, arriving at the island since then called Ireland, and landing in that part of it now called Munster, left his son with fifty of his men to guard the ship, and with the rest travelled about the island. Informed, among other things, that the three sons of Cearmad, called Mac-Cuill, MacCeacht, and MacGreine, did then and for thirty years before rule and govern the island, each for one year, in his turn; and that the country was called after the names of their three queens--Eire, Fodhla, and Banbha, respectively: one year called "Eire," the next "Fodhla," and the next "Banbha," as their husbands reigned in their regular turns; by which names the island is ever since indifferently called, but most commonly "Eire,"because that MacCuill, the husband of Eire, ruled and governed the country in his turn the year that the Clan-na-Milé (or the sons of Milesius) arrived in and conquered Ireland. And being further informed that the three brothers were then at their palace at Aileach Neid, in the north part of the country, engaged in the settlement of some disputes concerning their family jewels, Ithe directed his course thither; sending orders to his son to sail about with his ship and the rest of his men, and meet him there.

When Ithe arrived where the (Danan) brothers were, he was honourably received and entertained by them; and, finding him to be a man of great wisdom and knowledge, they referred their disputes to him for decision. That decision having met their entire satisfaction, Ithe exhorted them to mutual love, peace, and forbearance; adding much in praise of their delightful, pleasant, and fruitful country; and then took his leave, to return to his ship, and go back to Spain.

No sooner was he gone than the brothers began to reflect on the high commendations which Ithe gave of the Island; and, suspecting his design of bringing others to invade it, resolved to prevent them, and therefore pursued him with a strong party, overtook him, fought and routed his men and wounded himself to death (before his son or the rest of his men left on ship-board could come to his rescue) at a place called, from that fight and his name, Magh Ithe or "The plain of Ithe" (an extensive plain in the barony of Raphoe, county Donegal); whence his son, having found him in that condition, brought his dead and mangled body back into Spain, and there exposed it to public view, thereby to excite his friends and relations to avenge his murder.

And here I think it not amiss to notify what the Irish chroniclers, observe upon this matter, viz.--that all the invaders and planters of Ireland, namely, Partholan, Neimhedh, the Firbolgs, Tuatha-de-Danans, and Clan-na-Milé, where originally Scythians, of the line of Japhet, who had the language called Bearla-Tobbai or Gaoidhilg [Gaelic] common amongst them all; and consequently not to be wondered at, that Ithe and the Tuatha-de-Danans understood one another without an Interpreter--both speaking the same language, though perhaps with some difference in the accent.

The exposing of the dead body of Ithe had the desired effect; for, thereupon, Milesius made great preparations in order to invade Ireland--as well to avenge his uncle's death, as also in obedience to the will of his gods, signified by the prophecy of Cachear, aforesaid. But, before he could effect that object, he died, leaving the care and charge of that expedition upon his eight legitimate sons by his two wives before mentioned.

Milesius was a very valiant champion, a great warrior, and fortunate and prosperous in all his undertakings: witness his name of "Milesius," given him from the many battles (some say a thousand, which the word "Milé" signifies in Irish as well as in Latin) which he victoriously fought and won, as well in Spain, as in all the other countries and kingdoms he traversed in his younger days.

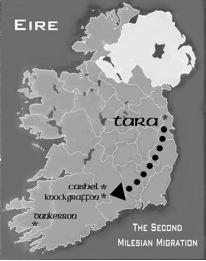

The eight brothers were neither forgetful nor negligent in the execution of their father's command; but, soon after his death, with a numerous fleet well manned and equipped, set forth from Breoghan's Tower or Brigantia (now Corunna) in Galicia, in Spain, and sailed prosperously to the coasts of Ireland or Inis-Fail, where they met many difficulties and various chances before they could land: occasioned by the diabolical arts, sorceries, and enchantments used by the Tuatha-de-Danans, to obstruct their landing; for, by their magic art, they enchanted the island so as to appear to the Milesians or Clan-na-Milé in the form of a Hog, and no way to come at it (whence the island, among the many other names it had before, was called Muc-Inis or "The Hog Island"); and withal raised so great a storm, that the Milesian fleet was thereby totally dispersed and many of them cast away, wherein five of the eight brothers, sons of Milesius, lost their lives.

That part of the fleet commanded by Heber, Heremon, and Amergin (the three surviving brothers), and Heber Donn, son of Ir (one of the brothers lost in the storm), overcame all opposition, landed safe, fought and routed the three Tuatha-de Danan Kings at Slieve-Mis, and thence pursued and overtook them at Tailten, where another bloody battle was fought; wherein the three (Tuatha-de-Danan) Kings and their Queens were slain, and their army utterly routed and destroyed: so that they could never after give any opposition to the Clan-na-Milé in their new conquest; who, having thus sufficiently avenged the death of their great uncle Ithe, gained the possession of the country foretold them by Cachear, some ages past, as already mentioned.

Heber and Heremon, the chief leading men remaining of the eight brothers, sons of Milesius aforesaid, divided the kingdom between them (allotting a proportion of land to their brother Amergin, who was their Arch-priest, Druid, or magician; and to their nephew Heber Donn, and to the rest of their chief commanders), and became jointly the first of one hundred and eighty-three Kings or sole Monarchs of the Gaelic, Milesian, or Scottish Race, that ruled and governed Ireland, successively, for two thousand eight hundred and eighty-five years from the first year of their reign, Anno Mundi three thousand five hundred, to their submission to the Crown of England in the person of King Henry the Second; who, being also of the Milesian Race by Maude, his mother, was lineally descended from Fergus Mor MacEarca, first King of Scotland, who was descended from the said Heremon--so that the succession may be truly said to continue in the Milesian Blood from before Christ one thousand six hundred and ninety-nine years down to the present time.

Heber and Heremon reigned jointly one year only, when, upon a difference between their ambitious wives, they quarreled and fought a battle at Ardcath or Geshill (Geashill, near Tullamore in the King's County), where Heber was slain by Heremon; and, soon after, Amergin, who claimed an equal share in the government, was, in another battle fought between them, likewise slain by Heremon. Thus, Heremon became sole Monarch, and made a new division of the land amongst his comrades and friends, viz.: the south part, now called Munster, he gave to his brother Heber's four sons, Er, Orba, Feron, and Fergna; the north part, now Ulster, he gave to Ir's only son Heber Donn; the east part or Coigeadh Galian, now called Leinster, he gave to Criomthann-sciath-bheil, one of his commanders; and the west part, now called Connaught, Heremon gave to Un-Mac-Oigge, another of his commanders; allotting a part of Munster to Lughaidh (the son of Ithe, the first Milesian discoverer of Ireland), amongst his brother Heber's sons.

From these three brothers, Heber, Ir, and Heremon (Amergin dying without issue), are descended all the Milesian Irish of Ireland and Scotland, viz.: from Heber, the eldest brother, the provincial Kings of Munster (of whom thirty-eight were sole Monarchs of Ireland), and most of the nobility and gentry of Munster, and many noble families in Scotland, are descended. From Ir, the second brother, all the provincial Kings of Ulster (of whom twenty-six were sole Monarchs of Ireland), and all the ancient nobility and gentry of Ulster, and many noble families in Leinster, Munster, and Connaught, derive their pedigrees; and, in Scotland, the Clan-na-Rory--the descendants of an eminent man, named Ruadhri or Roderick, who was Monarch of Ireland for seventy years (viz., from Before Christ 288 to 218).

From Heremon, the youngest of the three brothers, were descended one hundred and fourteen sole Monarchs of Ireland: the provincial Kings and Hermonian nobility and gentry of Leinster, Connaught, Meath, Orgiall, Tirowen, Tirconnell, and Clan-na-boy; the Kings of Dalriada; all the Kings of Scotland from Fergus. Mor MacEarca down to the Stuarts; and the Kings and Queens of England from Henry the Second down to the present time.

The issue of Ithe is not accounted among the Milesian Irish or Clan-na-Milé, as not being descended from Milesius, but from his uncle Ithe; of whose posterity there were also some Monarchs of Ireland (see Roll of the Irish Monarchs, infra), and many provincial or half provincial Kings of Munster: that country upon its first division being allocated to the sons of Heber and to Lughaidh, son of Ithe, whose posterity continued there accordingly.

This invasion, conquest, or plantation of Ireland by the Milesian or Scottish Nation took place in the Year of the World three thousand five hundred, or the next year after Solomon began the foundation of the Temple of Jerusalem, and one thousand six hundred and ninety-nine years before the Nativity of our Savior Jesus Christ; which, according to the Irish computation of Time, occurred Anno Mundi five thousand one hundred and ninety-nine: therein agreeing with the Septuagint, Roman Martyrologies, Eusebius, Orosius, and other ancient authors; which computation the ancient Irish chroniclers exactly observed in their Books of the Reigns of the Monarchs of Ireland, and other Antiquities of that Kingdom; out of which the Roll of the Monarchs of Ireland, from the beginning of the Milesian Monarchy to their submission to King Henry the Second of England, a Prince of their own Blood, is exactly collected.

[As the Milesian invasion of Ireland took place the next year after the laying of the foundation of the Temple of Jerusalem by Solomon, King of Israel, we may infer that Solomon was contemporary with Milesius of Spain; and that the Pharaoh King of Egypt, who (1 Kings iii. 1,) gave his daughter in marriage to Solomon, was the Pharaoh who conferred on Milesius of Spain the hand of another daughter Scotia.]

Milesius of Spain bore three Lions in his shield and standard, for the following reasons; namely, that, in his travels in his younger clays into foreign countries, passing through Africa, he, by his cunning and valor, killed in one morning three Lions; and that, in memory of so noble and valiant an exploit, he always after bore three Lions on his shield, which his two surviving sons Heber and Heremon, and his grandson Heber Donn, son of Ir, after their conquest of Ireland, divided amongst them, as well as they did the country: each of them bearing a Lion in his shield and banner, but of different colors; which the Chiefs of their posterity continue to this day: some with additions and differences; others plain and entire as they had it from their ancestors.

37. Ir: his son. This Prince was one of the chief leaders of the expedition undertaken for the conquest of Erinn, but was doomed never to set foot on the "Sacred Isle;" a violent storm scattered the fleet as it was coasting round the island in search of a landing place, the vessel commanded by him was separated from the rest of the fleet and driven upon the island since called Scellig-Mhicheal, off the Kerry coast, where it split on a rock and sank with all on board, B.C. 1700.

38. Heber Donn: his son; born in Spain; was granted by Heber and Heremon the possession of the northern part of Ireland, now called Ulster.

39. Hebric: his son; was killed in a domestic quarrel.

40. Artra: his youngest son; succeeded in the government of Uladh or Ulster; his elder brothers, Cearmna and Sobhrach, put forth their claims to sovereign authority, gave battle to the Monarch Eochaidh, whom they slew and then mounted his throne; they were at length slain: Sobhrach at Dun Sobhrach, or "Dunseverick," in the county of Antrim, by Eochaidh Meann; and Cearmna (in a sanguinary battle fought near Dun Cearmna, now called the Old Head at Kinsale, in the county of Cork, where he had his residence), by his successor Eochaidh Faobhar-glas, grandson of Heber Fionn, B.C. 1492.

41. Artrach: son of Artra.

42. Sedna: his son; slew Rotheacta, son of Maoin, of the race of Heremon, Monarch of Ireland, and, mounting his throne, became the 23rd Monarch. It was during his reign that the Dubhloingeas or "pirates of the black fleet" came to plunder the royal palace of Cruachan in Roscommon, and the King was slain, in an encounter with those plunderers, by his own son and successor, who mistook his father for a pirate chief whom he had slain and whose helmet he wore.

43. Fiacha Fionn Scothach, the 24th Monarch: son of Sedna; so called from the abundance of white flowers with which every plain in Erinn abounded during his reign; was born in the palace of Rath-Cruachan, B.C. 1402; and slain, B.C. 1332, in the 20th year of his reign, by Munmoin, of the Line of Heber.

44. Eochaidh (2): his son; better known as Ollamh Fodhla, i.e., "Ollamh, or chief poet of Fodhla" (or Ireland); began his reign, A.M. 3882, B.C. 1317 (according to the received computation of the Sep-tuagint, making A.D. 1 agree with A.M. 5199). This Eochaidh was the 27th Monarch of Ireland, and reigned 40 years. It was this Monarch who first instituted the Feis Teamhrach (or "Parliament of Tara"), which met about the time called "Samhuin" (or 1st of November) for making laws, reforming general abuses, revising antiquities, genealogies, and chronicles, and purging them from all corruption and falsehood that might have been foisted into them since the last meeting. This Triennial Convention was the first Parliament of which we have any record on the face of the globe; and was strictly observed from its first institution to A.D. 1172; and, even as late as A.D. 1258, we read in our native Annals of an Irish Parliament, at or near Newry. (See "O'Neill" Stem, No. 113.) It was this Monarch who built Mur Ollamhan at Teamhair (which means "Ollamh's fort at Tara"); he also appointed a chieftain over every cantred and a brughaidh over every townland.

According to some chroniclers, "Ulster" was first called Uladh, from Ollamh Fodhla. His posterity maintained themselves in the Monarchy of Ireland for 250 years, without any of the two other septs of Heber and Heremon intercepting them. He died at an advanced age, A.M. 3922, at his own Mur (or house) at Tara, leaving five sons, viz.: 1. Slanoll; 2. Finachta Fionnsneachta (or Elim); 3. Gead Ollghothach, and 4. Fiacha, who were successively Monarchs of Ireland; and 5. Cairbre.

45. Cairbre: son of Ollamh Fodhla; King of Uladh; d. in the 22nd year of the reign of his brother Fiacha.

46. Labhradh: his son; governed Ulster during the long reign of his cousin Oiliol, son of Slanoll.

47. Bratha: his son; was slain by Breasrigh, a prince of the Heberian race, in the 12th year of the reign of Nuadhas Fionn-Fail.

48. Fionn: his son; fought against the Monarch Eochaidh Apach at Tara, defeated him, and became the 42nd Monarch; but after a reign of 22 years was slain by Seidnae Innaraidh, his successor.

49. Siorlamh: his son; so called from the extraordinary length of his hands (Lat. "longimanus," or long-handed); slew the Monarch Lugbaidh Iardhonn, and assumed the sovereignty of the kingdom, which he held for 16 years, at the expiration of which, in B.C. 855, he was slain by Eochaidh Uarceas, son of the former King.

50. Argeadmar (or Argethamar): his son; ascended the Throne of Ireland, B.C. 777, and was the 58th Monarch; after a reign of 30 years, was slain by Duach Ladhrach. He left four sons: 1. Fiontan, whose son, Ciombaoth, was the 63rd Monarch; 2. Diomain, whose son, Dithorba, became the 62nd Monarch; 3. Badhum, who was father of Aodh Ruadh, the 61st Monarch, who was drowned at Eas Ruadh (or Assaroe), now Ballyshannon, in the county of Donegal, and grandfather of Macha Mongruadh, or "Macha of the Golden Tresses," the 64th Monarch, and the only queen Ireland ever has had, who laid the foundation of the Royal Palace of Emania, in the county of Armagh, where her consort Cimbath, died of the plague; the fourth son of Argeadmar was Fomhar.

51. Fomhar: son of Argeadmar; died during the reign of Cimbath.

52. Dubh: his son; was King of Ulster.

53. Eos: his son.

54. Srubh: his son.

55. Indereach: his son.

56. Glas: his son.

57. Carbre (or Cathair): his son.

58. Feabhardhile: his son.

59. Fomhar (2): his son.

60. Dubh (2): his son.

61. Sithrich: his son.

62. Ruadhri (or Rory) Mór: his son; was the 86th Monarch; died B.C. 218. From him the "Clan-na-Rory" were so called. He left, amongst other children 1. Bresal Bodhiobha, and 2. Congall Clareineach, who were respectively the 88th and the 90th Monarchs; 3. Conragh, the father of the 105th Monarch Eiliomh; 4. Fachna Fathach, the 92nd Monarch, who, by his wife Neasa was father of Conor; 5. Ros Ruadh, who by his wife Roigh, the father of the celebrated Fergus Mór; and 6. Cionga, the ancestor of the heroic Conal Cearnach,from whom are descended O'Moore, MacGuinness, M'Gowan, and several other powerful families in Ulster and Conacht.

63. Ros Ruadh: son of Rory Mór; m. Roigh, dau. of an Ulster Prince – Brother to 63. Cionga: son of Rory Mór. ( Cionog (or Cionga), brother of Ros who is No. 63 on the "Line of Ir," was the ancestor of MacAonghuis [oneesh]; anglicised MacGuinness, Maginnis, Magennis, Magenis, MacInnes, Guinness, Angus, Ennis, Innis, etc.)

64. Capa (or Cathbharr): his son.

65. Fachna Fathach: his son; the 92nd Monarch of Ireland.

66. Cas: his son; and brother of Conor MacNessa, who deposed Fergus MacRoy from the sovereignty of Ulster.

67. Amergin: his son.

68. Conall Cearnach: his son; the famous warrior, so often mentioned in the Irish Annals as connected with the Red Branch Knights of Ulster.

69. Irial Glunmhar & Lioseach Lannmor: son of Conall Cearnach.: his son; King of Ulster; had a brother named Laoiseach Lannmor, who was also called Lysach, and who was the ancestor of O'Moore

70. Lugha-Laoghseach: his son.

71. Lugha-Longach: his son.

72. Baccan: his son; a quo Rath-Baccain.

73. Earc: his son.

74. Guaire: his son.

75. Eoghan (or Owen): his son.

76. Lugna: his son.

77. Cuirc: his son.

78. Cormac: his son.

79. Carthann: his son.

80. Seirbealagh: his son.

81. Bearrach: his son.

82. Nadsier: his son.

83. Aongus: his son.

84. Aongus (2): his son.

85. Beannaigh: his son.

86. Bearnach: his son.

87. Maolaighin: his son.

88. Meisgil: his son.

89. Eochagan: his son.

90. Cathal (or Charles): his son.

91. Cionaodh: his son.

92. Gaothin Mordha: his son; the first King of Lease (or Leix), now the "Queen's County."

93. Cinnedeach: his son.

94. Cearnach: his son.

95. Maolmordha ("mordha:" Irish, proud): his son; a quo O'Maoilmordha.

96. Cenneth: his son.

97. Cearnach (2): his son.

98. Cenneth (3): his son.

99. Faolan: his son.

100. Amergin: his son; who is considered the ancestor of Bergin.

101. Lioseach: his son.

102. Donall: his son.

103. Conor Cucoigcriche: his son.

104. Lioseach (2): his son.

105. Donall (or Daniel) O'Moore: his son; King of Leix or Lease; first assumed this surname.

106. Daniel Oge: his son.

107. Lioseach (3): his son; the last "King of Lease;" built the Monastery of Lease (called De-Lege-Dei), A.D. 1183.

108. Mall (or Neal): his son.

109. Lioseach (4): his son; had a brother named Daniel.

110. David: son of Lioseach.

111. Anthony: his son.

112. Melaghlin: his son; died in 1481.

113. Connall: his son; d. in l518.

114. Roger Caoch: his son; was slain by his brother Philip; had a brother named Cedagh, who died without issue; and a younger brother named John, who was the ancestor of Mulchay.

115. Charles O'Moore, of Ballinea (now Ballyna), Enfield: son of Roger Caoch; d. 1601; had an elder brother named Cedagh, who was Page to Queen Elizabeth, who granted him Ballinea.

116. Col. Roger, son of Charles; d. 1646; had a brother named Anthony.

117. Col. Charles: his son; Governor of Athlone; killed in the Battle of Aughrim, 12th July, 1691; his sister Anne was wife of Patrick Sarsfield of Lucan, and mother of Patrick, earl of Lucan.

118. Lewis: his son; d. 1738.

119. James O'Moore; his son;

whose daughter and sole heir, Letitia, married Richard O'Farrell, of Ballinree, county Longford.

120. Ambrose O'Farrell, of Ballyna: their son.

121. Richard Moore O'Farrell: his son; b. in 1797, d. 1880.

122. Ambrose More O'Ferrall, of Ballyna House, Enfield, co. Kildare; his son; living in 1887.

The Legendary Breoghan

Lamhfionn was a son of Agnon. He and his little fleet remained at sea for some time, resting and refreshing themselves on various islands. At that time Cachear their Druid, or priest, predicted that they would continue to wander until they reached the Western Island of Europe, now called Ireland. They would not reach Ireland themselves, but their descendants would after 300 years. Eventually Lamhfionn and his fleet reached Libya, at the point where Carthage was later built. Soon after, Lamhfionn died in Libya. Heber Glunfionn, son of Lamhfionn, was born and died in Libya. He was the father of Agnan Fionn. Heber Glunfionn and his posterity were kings and rulers there for over 150 years. Some sources say it was up to 300 years. Agnan Fionn was the father of Febric Glas. Febric Glas was the father of Nenuall. Nenuall was the father of Nuadhad. Nuadhad was the father of Alladh. Alladh was the father of Arcadh.

Arcadh was the father of Deag. Deag was the father of Brath, who was born in Libya (called Gothia or Getulia). Remembering Cachear’s prediction, Brath departed Libya with a large fleet to seek the Western Island of Europe, Ireland. After some time, Brath landed in Spain, and established a colony in Galicia in northern Spain. Breoghan (or Brigus) was a son of Deag. Breoghan's descendant was the legendary Connal Cearnach ; which eventually Conal or Connal became the founder of Clan Mordha/ O'Mordha (Moore/ O'Moore). He conquered Galicia, Andalusia, Murcia, Castile, and Portugal. He built Breoghan’s Tower in Galicia. He also sent a colony into Britain, and their descendants gave formidable opposition to the Romans as they invaded Britain.

Bile was a son of Breoghan, and he became king of all the countries his father had conquered. Bile had a brother named Ithe, of whom more will be said later. The Great Warrior of Milesius was a son of Breoghan. In his youth, Milesius traveled to Scythia. The King of Scythia gave him the hand of his daughter in marriage and appointed him General of his army. Milesius defeated the king’s enemies and became very popular with the people, so much so that the King became jealous and resolved to kill Milesius. Milesius discovered the King’s plot and killed the King instead. Then Milesius left Scythia with a fleet of sixty ships, and upon his arrival in Egypt, Pharoah Nectonibus made him General of all his forces against the King of Ethiopia.

Milesius was victorious. Milesius was a widower by this time, so in gratitude, Nectonibus gave Milesius the hand of his daughter Scotia in marriage. Milesius remained in Egypt for eight years, during which time he had his most able people instructed in the arts and sciences of Egypt, so that they might teach others when they returned to Spain.Eventually, Milesius returned to Spain. There, he found that the country had been overrun by "foreigners". By a series of fifty-four battles, Milesius drove the foreigners from Spain, and then settled down to rule in peace and quiet. However, a famine of twenty-six years duration fell upon Spain. The reasons for the famine were the lack of rainfall and the fact that the people had failed to use enough manure on their fields, but Milesius was superstitious and believed that his failure to seek the Western Island (Ireland) of Europe was the cause of the famine.

Knowing that the 300 years predicted by Cachear the Druid was about to expire, Milesius sent his uncle Ithe and Ithe’s son Lughaidh and 150 others to bring back an account of the Western Island. When he landed in the Western Island, or Ireland, Ithe left Lughaidh and 50 men to guard the ship while Ithe and the other 100 men explored. Ithe learned that the three rulers of Ireland were at their palace at Aileach Neid. Ithe travelled overland to Aileach Neid, sending word to Lughaidh to bring the ship around with the rest of the men. When Ithe arrived at Aileach Neid, he was honorably received and entertained, and then Ithe started back to his ship to return to Spain.

However, the three rulers suspected that Ithe would bring others from Spain to invade Ireland, so they attacked and killed Ithe before he reached the ship. This happened at Magh Ithe, or the Plain of Ithe. Lughaidh recovered his father’s body and returned it to Spain, where it was put on public display to excite the people to avenge Ithe’s death. Some sources say that Ithe was only wounded ashore, but died during the voyage back to Spain. Both in obedience to the God as signified by Cachear, and to avenge his uncle’s death, Milesius made preparations to invade Ireland. He died before the expedition got underway, leaving the invasion of Ireland to his eight sons by his two wives.

The Migration of the Milesian Tribe

Around 1550 BC, the king of Scythia was Phoeniusa Farsaidh [1]*, an enlightened despot whose interest in ruling his people paled in comparison to his thirst for knowledge. His dream was to study and master all of the languages of the people in that part of the world. With this objective in mind, he surrendered his throne to his oldest son, Nenuall, and moved south to the City of Aeothena, in the Valley of Senaar. (Shinar, the plain in the Tigris and Euphrates basin.) He brought with him a younger son, Niul [2], who remained with his father in exile for twenty years. This move was the Third Adamic Migration

Soon after Asruth passed away, local politics changed and the Scythians were perceived by the Pharaoh as being subversive. A series of battles and bitter conflicts ensued during which a great number of the Scythians were killed. Outnumbered and out armed, Sruth was forced to abandon Capacyront with his small band of survivors. They escaped Egypt by boat and eventually landed on the island of Crete. Sruth died soon after their arrival. This exodus of the tribe of Gaodhal (Gael) resulted in the First Gaelic Migration.

Heber Scut [6]*, oldest son of Sruth, stayed on Crete for about one year where he served as king of his people. He held a council and announced his intentions of returning to Scythia. Some of his people opted to stay on Crete and it is likely that a branch of Gaodhal’s bloodline still remains there since "the island breeds no venomous serpent ever since."Internecine battles continued between the two royal houses and in one engagement Heber was slain by Noemus, the former king’s son. Beouman [7]*, Ogaman [8]*, and Tait [9]*, were all, in turn, the oldest sons of the line of Heber and all served as kings of Scythia. After Tait’s death, however, Prince Agnon [10] was unable to retain the throne and he was forced to abandon Scythia and roam the Caspian Sea for several years as a dispossessed brigand. Agnon would never settle back on land again and he died at sea. His oldest son, Lamhfionn [11], became chief of this marauding band of pirates. This exile of the Gaels from Scythia was the Third Gaelic Migration.

One day, Caicher, the druid of the clan, approached his chief and shared with him a vision that he had seen. He told Lamhfionn of a distant western island that was green and fertile. It was the ‘promised land’ for their people and he predicted that they would have no peace until they arrived on its shores. After much deliberation and prayer, Lamhfionn announced that they were abandoning the pirate’s life on the Caspian Sea and they were headed west in search of Caicher’s prophesied island.

They traversed the Caucasus Mountains, the Black Sea, and the Mediterranean Sea. At last they arrived at Gothia (or Getulia) which is now known as Libya. They settled along the Gulf of Tunis where Carthage would later be built and began subjugating the natives. Lamhfionn’s oldest son, Heber Glunfionn [12]*, was born in Gothia. After his father’s death he assumed command of the Scythians and continued winning battles over the indigenous Gothians. He was the first of his line to be crowned king of Gothia. This invasion of northern Africa by the Gaels comprised the Fourth Gaelic Migration.

He was reminded of the divine mission to bring his people to the ‘promised land’ on the mythical distant western island. The small band of Scythian nomads had grown into a strong and populous tribe while ruling over Gothia. Though Gothia had proven to be a fortuitous stop-over, it was not the final destination for the clan. A large fleet was built and the entire tribe left Africa and sailed to the coast of Spain. Brath was successful in establishing a fortified colony in Galicia, in the northwestern corner of the Iberian Peninsula. This transplantation of the Gaels to Spain was the Fifth Gaelic Migration.

Bile’s oldest son, Milesius Galamh [23]*, grew up hearing Ithe’s tales and, being the adventurous type, yearned to visit the ancestral lands of Scythia. When he was old enough to travel he assembled a small fleet and with his father’s blessings sailed off to the east. He received a warm welcome from the king of Scythia and married one of his daughters with whom he sired several sons.

His military abilities soon impressed the king and he appointed Milesius to be General of his armies. After many victories Milesius was a favorite among the Scythian people and this raised the jealousy and suspicion of the king. The king tried to have Milesius assassinated but the plan back-fired and Milesius in turn killed his father-in-law. He was forced to leave the country and with a fleet of sixty ships he sailed to Egypt.At the time of his arrival, Egypt was under attack by the Ethiopian army. Milesius’ reputation for valor, strategy, and wisdom preceded him and the Pharaoh offered him the position of General of the Egyptian defense forces.

Milesius accepted and soundly routed the Ethiopians. Milesius thus won great favor in the Pharaoh’s court and married Princess Scota, one of the Pharaoh’s daughters. Between his first Scythian wife and Princess Scota, Milesius fathered eight sons.

One day, while hunting, Milesius encountered three lions all of which he slew alone. To commemorate this feat he added three lions to his personal cognizance already emblazoned with the thunderbolt and serpent of Gaodhal . For eight years Milesius remained in Egypt, being instructed in the sciences, arts, and trades of the time. At length a messenger from Spain arrived with instructions from the king to return home. Milesius bid farewell to the Pharaoh and set sail for Galicia.

The next morning Milesius was shocked to hear his uncle Ithe describe a vision that he had in which he saw the fertile shores of the western island in the distance from the heights of Breoghan’s tower. It was a sign from Go Lear, their god, to abandon Spain and to pursue their destiny. (To this day there is a belief in Galicia, Spain, that one can see Ireland from the top of an old Roman lighthouse if the weather is clear.)

Ithe was instructed to assemble a fleet and to leave the kingdom at once to find Caicher’s island. Ithe, with his son, Lughaidh and one hundred and fifty hearty men, then sailed north to the Kenmare River, Kerry, Ireland.

The exact date of the arrival of the Gaelic Celts in Ireland is unknown; however, all credible sources maintain that it occurred before the age of Alexander the Great (356-323 BC). The dates cited in the ancient history of the clan are estimates based on the best available evidence. The Gaelic Celts dominated Ireland from the time of their arrival until the dawning of the thirteenth century. The Milesians were master equestrians, superior metal workers, and fierce warriors, traits that were common to all of the Magi tribes.

They were also gifted military strategists. True to their Scythian roots, they were tall, muscular, fair skinned, and light haired. The Gaelic Celts were distantly related to the continental Celts that sacked Rome in 387 BC, raided Delphi in 279 BC, and established the kingdom of Galatia in Asia Minor. They called themselves "Gaels", the word "Celt" being coined by latter day scholars to describe the loose confederation of Magi tribes that emanated from Scythia to conquer the indigenous peoples of Europe and the Middle East.

The Gaels originally divided Ireland into four provinces, Munster, Leinster, Ulster, and Connaught. Meath was not considered a province until a much later time. Although an Ard Ri, or high king, was recognized, his powers were very limited. The freedom loving Gaels forcefully resisted the establishment of a strong central government and preferred to retain most of the civil authority within their relatively small and semi-autonomous tribes.

Milesius, with the general approbation of his people, sent his uncle Ith, with his son Lughaidh, and one hundred and fifty stout men to bring them an account of the western Isles; who accordingly, arriving at the island called Ireland. The leader of this small expedition force, order his men to guard the ships, and the rest to traveled about the island. The natives called Dananns welcome Ith to Ireland, but the Dananns became suspicious about Ith's motives for coming to Ireland. Thru misunderstanding of Ith's motive; the Danann's king murder Ith and two of his brothers. The rest of Ith's men escape back to the ships with Ith and his brothers bodies, and sailed back to Galicia.

History of Clan Morè

Septs of Clan More of India

More, Madhure, Devkate, Harphale, Dhyber, Marathe, Darekar, Devkar, and Adavale.

Lands of Clan More

The Mor/ Mores lands in India belong to the family at one point.

Historic Seat More of Maharashtra- Capital of Latur More of Patna

More of Javali Jargir More of Mahipatgad

More of Kashmir More of Shivthar

More of Jor More of Jambhali

More of Mahipatgad More of Kevanle

More of Vakan More of Devali Tarf Ategaon

More of Devali More of Khelana ( Vishalgad)

More of Sakharwadi More of Tal Phaltan

More of Hadapsar More of Dhayari

More of Pune More of Mahabaleshwar

More of Parvat More of Chakdev

More of Ghonaspur More of Taldev

More of Gardev More of Dhardev

More of Moleshwar More of Bankot

More of Kandat Khore

The Mauryan Empire

The Mor/ Mur came to India and established the Mauryan empire. They were supposedly close kins of the Armorites of Babylonia and Egypt. The Jats immigrants are also close kins of the ancient Gatians of Sumeria and the Goths. he Mores are claiming descendants of the Mouryan Dynasty in which it defeated the Greeks, which was led by Alexander the Great. I also believe that the Mauryan Dynasty came from the Milesians, and below is a time period of kings of the Mauryan Dynasty.

Mauryan Dynasty (BCE320-300)

Chandragupta Maurya (BCE320-300)

Bindusar (BCE300-187)

Ashok (BCE273-232)

Kunal (BCE232-225)(From Ujjain)

Dasarath (BCE232-225)(From Patliputra)

Samprati(BCE225-?)

Saliska fl. late 3rd BCE.

Devadharm fl. late 3rd BCE.

Satamdhanu fl. early 2nd BCE.

Brihadrath(BCE194-187)

The More's were mostly known in the lands of Maharashtra from their king Akhilesh More of Latur. Their capital was at Latur. The area of then Javali Jagir stretched from Rairi Raigad fort was built by Chandrarao More in 1030 to Fort Khelana (Vishalgad) and Koyana Valley to the current Mumbai-Goa highway.

The following is a list of lands in which the More clan controlled and was in their possession.

1. More of Shivthar owned by Yashwantrao More

2. More of Jor owned by Hanmantrao More

3. More of Jambhali owned by Govindrao More

4. More of Mahipatgad owned by Dauloatrao More

5. More of Kevanale and Vakan owned by Bagrao More

6. More of Devali Tarf Ategaon owned by Suryarao More

7. More of Devali owned by Bhikajirao More

8. More of Khelana(Vishalgad) owned by Shankarrao More

9. More of Sakharwadi Tal.Phaltan and Hadapsar owned by Madhavrao Yashwantrao and Sadashivrao More 10.More of Dhayari, and Pune owned by Paresh Krishnaraj More

They were honored as Kings. The More families' jurisdiction extended over the region of Savitri Rivers to Mahabaleshwar, Parvat, Chakdev, Ghonaspur,Taldev, Gardev, Dhardev, Moleshwar, Bankot etc. Daulatrao More branch headquarters were at Kandat Khore, where they found Swayambhu Niripji Devi. The Daulatrao More from Mahipatgad was successor of title Chandrarao. The More clan will face an enemy that will invade the homeland of the Mores called Javali. Shivaji will end up defeating the Mores in a campaign that will bring the More clan to be one of the ninety six clans of the Maratha empire.

The Javali Campaign

Now, Javali was a strategically important to the region in which the Mores control. It was the gateway to the Konkan region. Javalia was a densely forested area, mainly comprising of eighteen valleys, called Khores. It was a region traditionally ruled by the Mores ( There are stories that More's were the descendants of the Somvanshi, king More of Kashmir, while other version claims descent from the Mauryas of Magadh.). They owed allegiance to the Adilshahi. Under the Mores came the Khores of Jambhul, Jor, Shivthar, Kandat, Tam, Bamnoli and others.

The Mores had a clan head called Chandraro. The last Chandraro More was Daulatrao. When he died he was issue with no heirs. Afzhal Khan, Adilshahs commander, wanted to annex the More's territory to the Adilshahi. So Daulatraos widower turned to Shivaji for help, and he provided her with the military support to help assert authority and to keep her relatives at bay. Yeshwantrao was adopted from within the More clan of Shivthar. Shivaji promised them to help against external aggression. Initially this Chandrarao More being indebted to Shivaji, professed loyalty towards him, but later he change his mind. His attitude towards Shivaji's officials and envoy to turned from polite to rude.

He also disrespected towards and also refuse to accept Shivaji as king, which ended up in an attack on Shivaji's supporters by the More clan. Shivaji, taken back by Chandrarao's sudden arrogance, and decided to teach him a lesson, by annexing his territory. It was a tough terrain, but Shivaji had local support. His supporters was Jedhes, Bandals and the Silimkars. On 27th January 1656. Shivaji's man Sambhaji Kavji and Raghunath Ballal Atre. Chandrarao and the Ghorpades of Mudhol, who besides being Shivajis rivals and relatives, were also Bijapur's officiers. At the end of the campaign; Shivaji ordered the execution of Chandrarao More and annex Javali. Soon after Javali fell, so did the forts of Wasota and Rairi were also in the hands of Shivaji's hands. Shivaji then instructed Moropant Pingale to construct a powerful fort for him within the vicinity of Javali. That the fort named as Pratapgad. Shivaji next acquisition was the fort of Rohida in May 1656. When the Javali campaign was over and now the Mores became part of the Shivaji's forces in which they help to establish the Maratha empire. The More clan also had septs that belong to the clan, includes the following names: Madhure, Devkate, Harphale, Dhyber, Devkar, and Adavale.

The Maratha and Mughal Empires War

The wars of the Maratha empire began as an imperial conquest, and were a series of conquest in the India subcontinent, which led to the rise of the Maratha empire with the enormous help from the More clan. The most important wars of the Maratha empire, was a war against the Mughal empire. The Mughal empire was indeed a very enormous empire that expands to the lands of Afghanistan, Bangladesh, India and Pakistan. Before the wars between the two empire; there was a war between the Maratha and the Adlishahi. The Battle of Pratapgad between the two forces. The battle was fought in 10th of November 1659, the beginning of the Maratha empire, which result in a decisive victory and major territorial gain for the Maratha forces, even thou they were outnumbered.

This war lasted about 27 years and had two wars between the Mughal and Maratha empires. The Maratha empire was small compare to the Mughal empire which was enormous. At first, it wasn't a large scale battles that were fought before the year of 1680. The war became intensify when Aurangzeb's invasion into the Maratha's lands in Bijapur, which was establish by Shivaji. In Bijapur there were three battles that were fought, which includes: 1. The Battle of Bijapur Sultanate 2. The Battle of Kolhapur 3. The Battle of Pawanhind

It was a long fought war involving a quarter of a century and innumerable long and short battles. The upcoming battles will be tough and bloody. Most of these battles that were fought by the Maratha forces, in which they were outnumbered, and became very victorious. Both side won many battles, and these two empires were fighting to dominate the whole country of India.

The Battle of Chakan

The Mughal emperor Aurangzeb was enraged with Shaistakhan as he was living in luxury in the Deccan. In spite of attacking and destroying the Maratha forces. He along with 30,000 troops laid siege to the Chakan fort. Firangoji Narsala along with only 6,000 troops; Maratha soldiers bravery repulse the massive force of the Mughal's army, which was led by Shaistakhan for months. Finally Shaistakhan blasted the walls of the fort by using explosives. The Mughal rushed inside the fort and killing many Maratha soldiers. Firangoji was finally capture and brought before Shaistakhan which eventually he let Firangoji go and he returned home.

The battle was over and the Mughal was victorious in defeating the Maratha in Chakan, Maharashtra. The next fight was to be taken at the battle of Umberkhind on 2nd February in 1661. The location of this battle was Pen, Maharashtra and it end up a decisive victory for the Marathas, and also at this battle the Mughal had to paid a huge tribute to the Maratha. Once again the Maratha were outnumbered. The next battle was to be fought was at Surat, Gujarat on 5th January in 1664.

The Battle of Surat

The Mughal's forces was composition of 1,000 men at the command of Inayat Khan. The Maratha forces was composition of 4,000 cavalry under the command of Shivaji. Shivaji attacked Surat after a demand for tribute was rejected by the Mughal's commander. The Mughal Sardar, not the bravest, was very surprised by the suddenness of the attack and not willing to face the Maratha forces, he had hid himself in the fort of Surat. However, there was an attempted assassination of Shivaji by the emissary sent by the Mughal's Sardar. So Shivaji took the city and sacked it. Surat was under attack for nearly three days, in which the Maratha army looted all possible wealth from the Mughal and Portuguese trading center. The total numbers of prisoners executed during the raid was four; the hands of others were cut off, which were 24 men. Shivaji had to complete the sacking of Surat before the Mughal empire at Deli was alerted and couldn't afford to waste much time in attacking. The Maratha won a decisive victory. The next battle to be fought was at Purandar.

The Battle of Purandar

The battle of Purandar was fought in the year of 1665 in Purandar, India. The battle of Purandar was fought between Mughal and Maratha empires. Aurangzeb sent his general Dilir Khan of a large Mughal forces, crossed the Narmada river, while Shivaji was still engage in mopping up operations on the Konkan coast. Dilir turned his attention to Puranda and Jay Singh moved his main force to attack Sinhagarth fort while lesser forces under his command were moving against the More of Rajgad and Lochagad. According to Dilir Khan's plan, he was to lay siege to Purandhar, which was then gaurded by Murar Baji, the Maratha governor.

Laying a siege to Shivaji's well guarded position wasn't so easy; methods which Shivaji's men adopted in defense were similar to those they used in attack. The method was always the same, namely to have a short and quick engagements with the enemy rather then to face him in pitch battle. The secret to Shivaji's success was that he adopted the methods of guerilla warfare and his men followed his example even when attacking at Purandhar. With his modest garrison of only 2,000 Mavalis and Hetkaris, Murar Baji staved off the Mughal's attack. He blocked every point of approach by sending out parties of stragglers whose tactics were to nibble at the Mughal forces rather than to face them four squares.

Dilir Khan was adamant in carrying out his plan. Determined to destroy this Maratha fortress, he decided to use gunpowder to mine the main rock on which the lower fort of Purandhar was built. He succeeded in doing this, but his follow through was resisted by the Mavalis. The Maratha troops open fire on their attackers from the upper fort and a fierce and desperate battle ensued. The Mughals charged along side with the Pathans and Afghans, with Diler Khan, himself, mounted on an elephant, directing the operation. The battle for Purandhar fort ended in a hand to hand combat.

At one stage, Murar Baji came so close to Diler Khan that they were even exchanging verbal threats at close quarters. Murar, deprived of his shield in battle, was struggling to strike at Diler with his sword. However, Diler, realising the desperateness of the situation, shot at Murar with his bow and arrow. The arrow killed the Maratha governor and as he died, his scattered forces retreat to the upper fort and close the gates. Timely assistance, however, came to the besieged garrison from Shivaji, who sent out an extra force, which announced it's arrival with trumpets and war drums. This Mughals hadn't anticipated and, taken by surprise by the reinforcements, which Shivaji had sent, Diler lost the early advantage, which he had gained.

The Mughal commander remained undaunted. The battle continued, but the forces of nature came to the assistance of Shivaji, for the monsoon rains broke over the battlefield, which greatly dislocated Diler's plans and disarrayed his forces. It was soon realised by Diler that the battle was merely leading to the loss of life without any progress being made towards the capture of the fort. Negotiations were thus renewed with Shivaji and a personal meeting was arranged between the Maratha and the Rajputs. Thus peace was restored by the means of a peace mission between the Marathas and the representatives of the Mughals.

At the battle of Purandar; the Maratha forces was victorious in holding out against the Mughal forces. Maratha also took victory at the battle of Kondhana, which was a night battle, but soon after the victory, the Mughals went on and winning at the following battles: Kalyan, Bhupalgarh and Sangammer. The Maratha went on after losing to the Mughals in three striaght battles in a row, went on winning at the following battles: Nesari and the southern campaign. At the southern campaign in southern India with a massive force of 50,000 strong, which includes 30,000 cavalry and 20,000 infantry. He defeated and capture forts at Vellore and Jini. He also signed a treaty with the Kulub Shah of Golconda. These victories against the Mughal empire was at the battles of Palkhed, Mandsour, Vasai, 1st battle of Delhi and Bhopal.

At this point of the war, it was going bad for the Mughal empire. The Maratha did an expidition to Bengal. The battles of Burdwan, 1st and 2nd battles of Katwa was won by the Bengal forces of the Mughal empire. Maratha finally won at the siege of Trichinopoly and at the capture of Delhi in 1757; the capital of Mughal. When the war between the Maratha and the Mughal forces finally ended. The Maratha empire had devastating blow to the Mughal empire, in which is now a small empire, due to lost of territories.

The Wars of Durrani and the British Empire

After defeating the Mughal empire in a series of conflicts and battles; the Maratha turned their attention on the Durrani empire, which is located in the northwest of India. The Maratha won a decisive victory against the Durrani empire, and annex their lands and added to the growing of the Maratha empire. They defeated the Durrani at the battle of Attack and at Peshawar. Later on the Maratha empire experience their first civil war in the years of 1762-63 in which the rebels were soundly defeated at the battle of Rakshasbhuvan. The Maratha empire is about to meet it's greatest threat, and another rising empire known as the British empire.